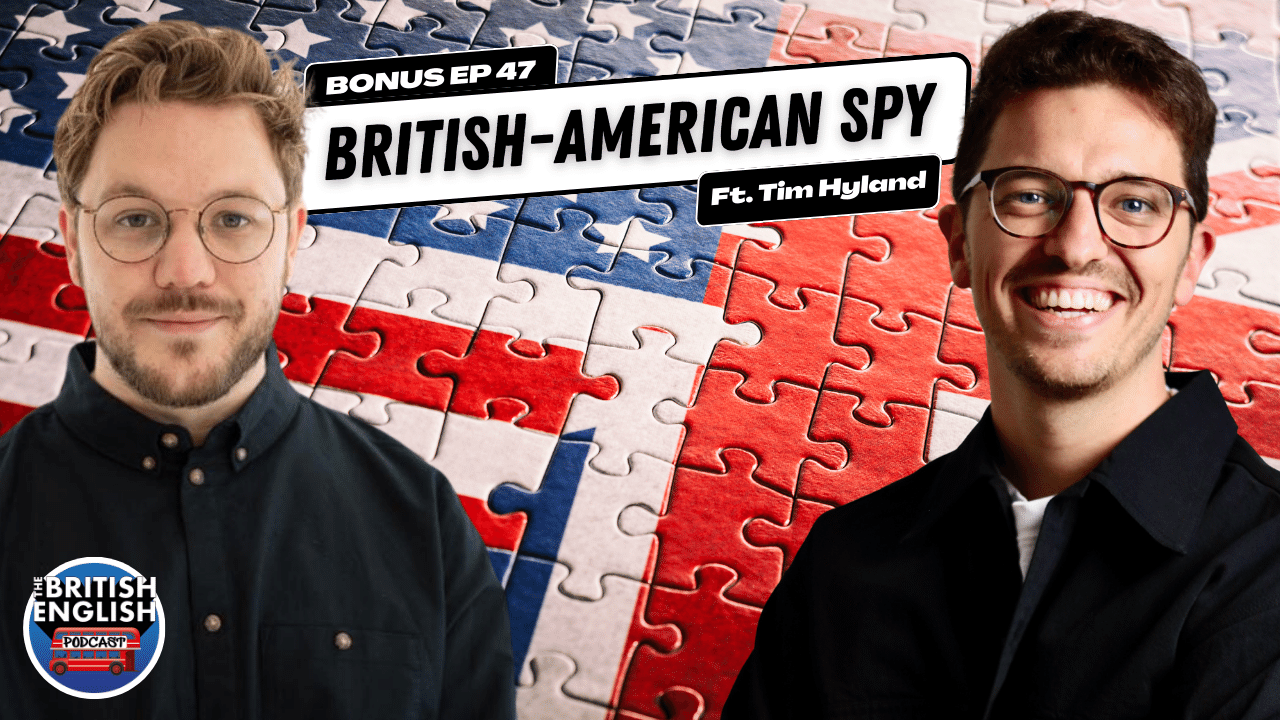

Bonus Ep 47 - Agent of Two Worlds, The Mysterious Life of a British-American Spy

Access your active membership's learning resources for this episode below:

Access your active membership's learning resources for this episode below:

What's this episode about?

Continue listening to this episode

Click Here & Enjoy!

Click Here & Enjoy!

Click Here & Enjoy!

Click Here & Enjoy!

Tim Hyland

Transcript of Premium Bonus 047- Transcript

Charlie:

Hello and welcome, ladies and gentlemen. Boys and girls. Well, no. Mainly ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, not really advised to listen to this because there's sometimes some swearing. But yes, welcome to yet another scintillating episode of the British English podcast. As always, I am your host, Charlie Baxter, ready to take you on a fascinating exploration of culture, language and the riveting places where they intersect. Today's theme agent of Two Worlds The Mysterious Life of a British American Spy. A deep dive into the unique experiences of those who've lived a life between the UK and the US went on a search for one of those people who really do see the 41.1 million square miles of Atlantic Ocean as a mere pond that they pop over whenever they feel like it, and found an individual who could well be a double agent. But which country is he truly serving? Hopefully, we won't need to torture him to get to the bottom of it. But whilst storming his flat in London and setting up two microphones, I did pack my trusty waterboarding rag and bucket just in case. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming our guest, a man who personifies the British American connection. Born to a British mother and an American father, a mr. Tim Hyland. Hello, sir. How are you doing today?

Tim:

Yeah, very good, thank you. That was an amazing intro.

Charlie:

Well, thank you for letting me take your flat. Yeah, Come in rudely and not kick me out. It was very British of you. Is that an admittance to what Secret Service you are actually truly working for?

Tim:

I tell you what, actually, I think it's quite American to just accept, particularly my family. You would just accept somebody coming in. It's the best of both worlds, of both anxieties to tell people to leave. No, you're welcome here for the next few hours. And then I'd like you to leave. [Okay] That's the English version.

Charlie:

Yeah. Good.

Charlie:

I've got a question for you. I mean, I've got loads, but to start with, I've got one that I've always wondered, considering you've obviously grown up with a cup of English breakfast tea in one hand and an American hot dog in the other. How does it taste? Dunking a hot dog in your tea. Do you encourage everyone to try it?

Tim:

100% encourage everybody to try it at least once in their life. I think it's the delicacy of a half-English, half-American person. We all have a forum that we speak about our dunking abilities on, and that's one of it. And it's delicious.

Charlie:

Yes, I imagine the liquid would drip quite quickly off the skin of a hot dog.

Tim:

You'd be surprised.

Charlie:

Okay, so apart from being astonished by the absorbance of a hot dog, can you share with us a bit about your upbringing and how did growing up with parents from two different cultures shape your early years?

Tim:

Absolutely. My.. So my mum is English. As you've sort of stated, my mum met my dad, my dad was stationed, he was a military man and he was stationed in a place called Mildenhall. And it's quite a big base American base in England.

Charlie:

Where is that?

Tim:

In England, In Suffolk, in East Anglia. [Okay] He sort of met my mum on a sort of night out. All the people from the RAF would go to the local nightclub. My mum met him. I think that's through the manner of which they met.

Charlie:

The RAF. They're an English, the Royal Air Force.

Tim:

Oh no. So it's actually AAFES which is the American Air Force.

Charlie:

What did you just say? Did you say..

Tim:

RAF. But that's just what we sort of refer to it as.

Charlie:

Oh, I see. So you used the British thing.

Tim:

That's an interesting thing I've never even thought about. We would say AAFES, which to be honest with you mate, I have absolutely no idea what it all means.

Charlie:

Sounds a bit weird to be honest. AAFEES.

Tim:

Exactly. That's why I don't use it.

Charlie:

RAF is very bold.

Tim:

Yeah. Plus, if I said Athies to you, you'd go. There's more questions.

Charlie:

Yes, we'd be here all night. So again, do you see that often? You know these cultural references and you adopt the right language for the right audience?

Tim:

I think more so growing up now, I'm sort of I've lived well, been in England more than America. I would say that I would adjust my my language more for the Americans than I would for the English. But there was a lot of times when we were younger, like Athies, like RAF, like even things like base, if you said, Oh, we're going on base this weekend, people would be like, What is base? And then I'd obviously have to go, Oh, okay, that's place where military stuff. Yeah.

Charlie:

Go back to where they met.

Tim:

They met in a little town called Newmarket. And basically it was a bit of an odd one, you know, because around that time in the 80s it was considered slightly odd for a lot of females would go to the base to marry an American man, to get out of the little town that they were in. That was kind of through the manner in which my mum was filtered, but that's what she experienced from other people. But that isn't actually what happened. [okay] And it kind of accidentally happened. They moved to Ipswich and my dad, we spent a lot of time on, you know, what was considered and what was often referred to as American soil, which was the base life, which was this incredible military base, which everything was American on it. So absolutely.

Charlie:

And it's in England.

Tim:

In England, there's a bunch of them around. [Wow] And they would have bowling alleys and restaurants and everything would be American. They would fly over ingredients.

Charlie:

We've got that - bowling alleys.

Tim:

Yeah, well, not American ones. [No]

Charlie:

What? So they would ship over the American-style bowling alleys?

Tim:

Yeah. And just absolutely everything you could think of they would fly over. They tried to make it as much home away from home as they could for the military men. We kind of, you know.

Charlie:

Did they like that? Because, you know, being abroad is quite an exciting part of life, isn't it?

Tim:

Yeah, it's it's an interesting one. I found this a lot with Dad. I think there's levels to which you can enjoy English culture and immerse yourself, but at the very foundation of it all, you are American and you love Taco Bell. So I think he really adopted clever. He loved pop culture, loved football, really adopted all these kind of things. But the reality was if he ate in a McDonald's in England and then he went half hour down the road to the base and ate the McDonald's there, it would taste completely different. [Wow] Yeah. Yeah. It's kind of [wow]

Charlie:

Well, so they actually shipped in different meat for that McDonald's. Do you think?

Tim:

That was a rumour amongst the RAF brats which we called ourselves. People who had to kind of toe this line of English and American culture.

Charlie:

That's so confusing.

Tim:

Yeah. The room was they would fly in and I think I reckon would be able to confirm it, but I don't know. But it's a better story, you know. [Oh yeah] Always print the legend. They would fly in the actual Taco Bell, meet the actual actual spices, everything.

Charlie:

Wow. Did you live in that environment or did you live outside of that?

Tim:

Yeah, 15 minutes outside of it. It was a choice that they both must have made to go.. when education came up. You can obviously, there's a school, a high school on base and there's football teams and there's, you know, everything.

Charlie:

And by football, what are we?

Tim:

American football. [American football]

Tim:

Yeah. [Wow] They would have absolutely everything that was potentially probably a big conversation that my mum and dad had that I obviously wasn't there for, and yet England was chosen.

Charlie:

But they didn't, surely wouldn't have gone to the extent of building wider roads and bigger cars.

Tim:

That's an interesting one because it was a military base. You would have this weird mixture of a lot of military vehicles and then a lot of the American military people serving the military would have cars all over. A lot of them wouldn't want to. So when you go back to these kind of places near bases like East Anglia, you will see like a pickup truck just randomly on the road with the wrong side, you know, the steering wheel on the wrong side and everything. I think you have to be really committed to the cause. If you're going to do that, you have to really.

Charlie:

Yeah. That's not just what do they call it? Not a stint. What's it called? A tour. Do you do tours to this place or do you live there? And then you go on a tour to an actual active country.

Tim:

I get the impression tour's when you go to a place of conflict, which my dad was very much involved with, did a lot of tours and England was where he was stationed. So I suppose because the massive difference being that this is a place to be be closer to Europe, to protect, have American bodies on ground, to protect Europe, basically.

Charlie:

God, it's such a different world. I mean, my parents, one of them is a teacher and one of them is a therapist. This is, I have no contact with Army life. I mean, my granddad was but I think all granddad's were to some extent, weren't they? Forced into it someway. [Yeah] Okay. So you grew up 15 minutes away from this American military base. [Yeah] And you went to a school that was English [Yeah] curriculum. British curriculum. But you had lots of American friends?

Tim:

Yeah, well, it's kind of difficult because I guess this is the point of the conversation. Like, the friends that I had were often half American and half English. [Of course] The ones who were taught on base would be what we called ourselves RAF brats and stuff. Military brats were more often than not half American, half English, and they, everything would be dictated by where they were educated. If they were educated on base, I'd have a lot of friends who were educated on base. They would all speak in an American accent and they would all be far more ingrained with American culture than they would English culture. And with us, because we were educated in England, literally 15 minutes down the road, all the same friends. We grew up going to the same gigs, going to the same nightclubs, doing all that kind of stuff. We spoke, you know, in an English accent and kind of immersed ourselves in quintessentially English things. And so it was just that very small differentiator. Living on the same in the same county, 15 minutes apart, but such a big distinctive on the surface thing, you know, American accent, English accent, dressed American dressed English, you know, all these kind of different nuances of culture. [Yeah] Yeah.

Charlie:

Did that ever cause conflict amongst peers? Like at that age, we're quite we're wanting to conform to the norm, aren't we? [Yeah] Did that make some people be like, What are you doing speaking American?

Tim:

Yeah, it was. What I found was a lot of the ones who had grown up with American accents, despite being in England, would really double down on their American accents. Okay, Really double down on it. I had a couple of friends called Tanya and Becky who literally like my, our dads worked together. You know, we lived not too far apart. We met in our kind of teen years and realised we were at the same bases and things like that, ate at the same places. They were very American compared to me and I remember speaking to them about this and being like, Why is it that you feel like you tried to retain that American accent despite clearly being surrounded by more English people? And they said that they themselves definitely doubled down on it, definitely found it was too confusing to have this weird accent that was a kind of transatlantic, you know, middle ground. They just chose sides. They just kind of adapted. Whereas for us it was slightly easier because I think it always became a bit more confusing when you would people would meet Dad or they would go, What are you doing this weekend? And I'd be, We're going to a barbecue on base or we're going to watch the football or whatever it might be. I think that's potentially where the confusion started coming in. And I think because American culture was so huge in the 90s the late 90s, American Pie was coming out and Blink182 was the biggest band and things like that.

Charlie:

American Pie is one of the biggest things of America that came out of America.

Tim:

There's a song about it that definitely helped the cultural influence.

Charlie:

Of Yeah, I know what you mean. Especially their music, I suppose. I wanted to ask about them. If they were sat here right now, would they say that they're American? Those two that doubled down on being American when they were ten or however old you were?

Tim:

Yeah, it's kind of interesting. Tanya stayed in London, lived in London, and Becky moved back to America. I feel like despite that, they would both still say American and their mum was English, their dad was American in the same situation as me. Sit me down here. I would say, I tend to say I'm English, but if there's a longer conversation, I'd say I'm actually half American. That's the kind of distinction. I think the base has a lot to account for for that kind of stuff.

Charlie:

Do you think accent is like a fingerprint of your identity or do you think we should negate that totally? Is that a very simplistic view?

Tim:

Good question. And and I want to answer it deeply, which is a problem. I think it's an interesting one because I've trained myself to not speak in this kind of weird amalgamation of Essex and East Anglia because once you, when you're growing up in Suffolk, you have an overspill of London and predominantly kind of particularly in Newmarket's horseracing towns, you have a lot of East End lads coming over to muck horses, so they all speak like this. Then you also have the Ipswich accent, which is quite like this, like a bit, kind of slightly Bristolian, but has a bit more of a kind of, you know. I had that kind of weird amalgamation for such a long time as well as these kind of weird Americanisms that my dad obviously kind of handed down to me. And the interesting thing is when you move into work and you start moving to London, you start meeting more people. There is a phenomenon, isn't there, which suggests that people start speaking more like the people around them and they adapt because they need to be accepted amongst the tribe. And I definitely feel like I did that about ten years ago. When you meet me and you meet my brother, my brother's "all right mate, how's it going?" type vibe. You meet my dad. I'm not going to do an accent of an American accent. Speaks like, I'm not going to do it. Speaks like an American.

Charlie:

But what kind of accent?

Charlie:

Southern?

Tim:

New York type. Not like New York, but like, just quite a gentle American accent. Transatlantic, almost. And he spent a lot of time in England, so he hasn't got the strongest American accent.

Charlie:

Would it have been a bit like Katie's? [Yeah] Because Katie's been on this show so.

Tim:

Very similar to Katie's.

Tim:

Katie's got a bit more of a kind of like she definitely got a bit more of a Californian spin to her accent, which makes it sound a bit more chilled out. But you put her in a queue or you put her in a busy stall and she turns into a classic New York, which I'm used to, which makes me feel immediately at home.

Charlie:

What's the summary of that to question of, does your accent represent your identity?

Tim:

Yeah, sorry. I think it's increasingly becoming more important because I think it expands far greater than the region in which you're from. I think it also relates to class and I think it relates to perhaps having multi nationality. And I think when I was growing up, we felt that we had to forcibly do something about it because it would become a conversation starter. And I do know a lot of friends who come from lots of different, amazing places had to kind of negate that accent a little bit, kind of reduce that accent, I suppose.

Charlie:

Do you think that was ten, 20 years ago and now it might be differently received, or do you think we're still in that state of judging an accent based on stereotypes?

Tim:

I hope so. I think the reduction of stereotypes helps contextually in popular culture, but I do find that in smaller towns like places like Newmarket, like even my nephew, who's a quarter American, and he refers to himself regularly as a quarter American to his friends, because I guess it's a nice little differentiator. Even when he says that, he said he's kind of still subject to a level of questioning, like a level of like, Oh, right, so what are you coming from like American granddad? And that that's weird to me. I'm like, Oh, okay. So we haven't completely leveled the playing ground yet. I presume in liberal metropolitan London it's easier, but in small kind of forgotten about towns in the East. I presume it's still the same old problems, you know?

Charlie:

Yeah, I guess if you've not got a melting pot of cultures to grow up around. [yeah, quite] Then that's the norm. And then you get used to that norm and then anything different and you respond like it's a strange thing.

Tim:

Yeah. Well that got political quick didn't it?

Charlie:

I just realised that I'm a quarter Australian. [Yeah] And I would support the Australian cricket team. [Wow. Yeah.] When in school and so I'd get stick if Australia ever lost The Ashes or something. Deep down I didn't actually care at all. But my dad always would be like, "go on Australia!" In that very British way. They didn't give me a hard time because I wasn't purely 100% British. They were just like, Oh, he's the one that lost, so let's give it to him.

Tim:

For kids, a differentiator, I suppose. Yeah, I'm not saying that word brilliantly, but differentiator between, isn't it? I guess you can claw onto anything, but yeah, I found it with him. He's doing the same thing to American and they go, Oh yeah, you know, something happens in America. They immediately jump on him, which is interesting. I didn't think it would. It would have any relevance to him, bless him. But it does. It continues.

Charlie:

I think we've kind of bled into some other questions, but let's see if we can get some more out of them. What were some of the noticeable differences between your life in the UK and your life in the US? Well, we haven't really touched on you actually going over to the US yet, so let's do that. So when was the first time you went over there?

Tim:

Oh, like very quickly after I was born. It was kind of like a Simba moment where I was shown to the family, taken over quite quickly.

Charlie:

Wow. Not in an army plane? [No] What are they called? Is there a special name for an Army plane?

Tim:

Military plane, I suppose.

Charlie:

Military plane. Easy.

Tim:

That's way boring. More boring than I was hoping for, actually. Yeah. Hopefully there's. Yeah, there is a word for it. It'll come to me. I'll just say it randomly in the next question. We got over there quite quickly because my granddad, my grandfather, grandpa, as I call him in America, is a Lutheran pastor. Like a like a pastor. Pastor. Yeah, yeah. That's, I guess.

Charlie:

Australians say pastor like that.

Tim:

Oh right really okay.

Charlie:

Because they've got a brand called Faster Pasta. But when I read it out loud as a Brit, I was like, Faster pasta. So rubbish. They're like, What? Faster Pasta? Well, that's American.

Tim:

Yeah, that sounded like my dad. There you go. We can just used that. My grandpa is like a vicar, I suppose. For the Lutheran church. And so it's very important for them religiously, which is an interesting, again, cultural signifier between England and and America, which maybe we'll touch on. But he's they're heavily religious and yeah, so he I think he wanted to get me instilled with the Lutheran church quite quickly which was my brother's happened both my brothers two older than me and my mum being the sneaky little Church of England lady that she is got me christened before I went over. So I went over there and they were shook to the core. She really that was like a mission impossible thing. And then they were like, Well, it's ruined now. I'm not gonna, we can't have him as part of the Lutheran church. They got me over there quite quickly. And then it was, you know, we sort of went over regularly, I'd say, you know, it was kind of in, in my childhood, I presume a good few times, like maybe five times over the course of ten years or whatever. Like every other year, I would say would be a healthy would be a healthy kind of, you know, suggestion.

Tim:

And then we went when we got into the older years, we would spend longer times out there when when I graduated, when I'd done my GCSEs, I suppose I'd graduated sixth form these big significant moments where you had a bit more time on your hands. We'd go out there summer holidays. We were out there, we travelled America because we had family everywhere. It was quite frequent, you know, frequent enough to be not confused by when you landed and by the American accents of your family, but not enough to build truly daily kind of relationships with extended family like uncles and aunts and stuff like that. I would have seen a handful of times I loved them. They're brilliant people and I think I know them well, but not compared to like my mum's friend who would be Auntie Julie, you know, in inverted commas, because we got more exposure to her. We got to see her more and she was a part of the family type thing. That was always quite interesting. So we went over there enough.

Charlie:

Yeah, definitely. I remember a friend used to always go over because his dad lived in America and before global warming, England didn't have very good summers and I would always get jealous of his days, sat by the pool day in and day out, just lapping up, and then he'd come back so brown. Also, I just realised a couple of weeks ago with Katie that Americans will always use the word tan. Get more tan or tanner. I'm tanner than you. Which is very strange. But we also. We say the word brown. Oh, you're so brown. Which, she was like, Oh, my God. You cannot say that now. Politically incorrect. Would.. how do you feel about that word?

Tim:

Wow, that's interesting. This is, I guess, the beauty of being from both worlds. Yeah, I can see both sides, you know. [But what would you say?] I would opt for, got a bit more brown. I've got a bit more. You know, I'd probably say tanned. Oh, look how brown I am.

Charlie:

Look how brown I am. That's normal.

Tim:

That doesn't feel particularly odd or misplaced to me. But then I think about how the Americans would react to that. And I go, Yeah.

Charlie:

Interesting, isn't it?

Tim:

Very interesting.

Charlie:

Yeah. You obviously could answer this with the military base being so close to you, but let's see. Do you have any childhood memories that particularly reflect the blend or fusion, if you will, of these two cultures? Don't know if you can go beyond the military base. That question.

Tim:

There's things like Thanksgiving and Christmas and actual festivities, which kind of especially when you're doing them in England, feel slightly alien when you're doing Thanksgiving in England compared to Thanksgiving in America. In America, it feels far more naturalistic, far more, kind of less forced and things like that. And in England there's still my mum's confused face going, Why are we doing this? Christmas is next month. So that was always slightly odd and Dad wouldn't push so much that on us. But when we did do that, I would notice it significantly. [right] And that was always a strange blend. I mean, I always found the blends of, I guess, just sort of popular culture and what people were into the sports of things and culture and political culture and actual social events that happened. They were always quite significantly different because you would be in England, but something significant would happen in America and you'd be treated differently for it. I remember when 911 happened and this big kind of cultural societal thing that was very significant across the news, all that kind of stuff happened and we were the only half American half English kids at our middle school at the time.

Tim:

So I remember a couple of teachers waiting at the gates for us and me and my brothers arrived and they went, come into this little room and they took us into a little room and they basically said, you know, has your family been affected? Were they in in the towers or anything? And I found it very strange because my family lived in Buffalo, New York, which was still New York. But to them, obviously, just they just heard the New York part. They didn't hear the Buffalo part. Buffalo is like near Canada. It was very strange to me for them as teachers to go to not know the kind of nuance of that and to and I remember that being a bit of a moment where I go, I feel English, but I'm clearly not because I've been like pulled into this side room to be to talk about this obviously awful thing and actually the reality was, was that my family were hours, hours away and didn't work in finance.

Charlie:

Wow. I mean, it's kind of like when, you know somebody from one city and you meet somebody and you're like, Oh, do you know John Smith?

Tim:

100%.

Charlie:

Kind of like that. So they're associating America with you.

Tim:

Yeah. Adults like, I remember being a child. [Yeah, that's crazy] And going, you know, and fair play for teachers have more on their mind than we've been affected by a tragedy that happened nine hours away. So I think they probably were just playing it safe. [Yes] Which was obviously nice. But I'd still remember that as being like, okay, so we're not the same as every other kid in this school. That is a slight odd blend. And when you put Thanksgiving and these national holidays aside, which we wouldn't get off but American kids would, that's always a bit strange as well. You know, you kind of go you see your American friends on base celebrating Thanksgiving and, you know, Independence Day and things like that. We're stuck in an English school who don't really talk about it.

Charlie:

Yeah, that's interesting. I noticed when living in America that the attitude towards how they would say costumes and we would say fancy dress is very different. If you were going to a Halloween party, would you go big or would you just put on a little bow tie and pretend you're some sort of clever person from a fictional story?

Tim:

Yeah, that option I choose the English option. [Yeah] Because again, another interesting thing about the town that we lived in was that there was like housing for military people nearby. So they would set them up in housing just 15 minutes down the road if they didn't want to be in base. They wanted to kind of integrate into English culture a little bit more, but they wanted to have like a four-storey house or whatever it might be, especially when you've got a big family. It's not easy to live on base. They sort of set people up when you would go to this very, very specific part of Newmarket, Halloween was completely different. There was massive lights everywhere you would go round and you would they would really celebrate it in a massive way. Everybody would be dressed up. It would predominantly be the Americans who really put it on, but the English would turn up in their terrible costumes. And also a lot of people from base and things like that. And it really felt like for that evening that was like the most American that town got it. You'd walk around and Halloween was a really, really big thing. And there was a couple of strange moments. Because it's a military base and once military bases are in danger,

Tim:

so if there's a conflict like in the Middle East or if something has happened, you know, something significant in military terms, they would the security would be heightened. All of a sudden, you would start being told you can only do it between 7 and 9, but they would really go hard for seven and nine type thing. That's the biggest thing. And that's I guess, why it's not too much of a cultural shock to see, you know, people that I know who are American and how much they love Halloween. [Yeah] Because we really grew up with it. But my mum, I remember one time my mum and I don't know whether this was a bit of a kind of kickback against American culture, but I remember she put bin bags on us all and then she put coat hangers on the bin bags and I went, What's this? And she went, I don't know, just gone. She was just being creative. She was just hanging things on us and I was walking around in this bin bag amongst all these American kids who were dressed incredibly. I think they sort of gave up on us at that point around that area.

Charlie:

There's an interesting blend there that, in my imagination, of you with your sort of more British mindset, having an egg in your pocket ready to throw it at a potential house that has not given you the right sweets or something, or they've given you some sweets and you just want to just egg somebody. And then a really over-the-top American dressed with like a a really, really scary ghost kind of. And you're walking hand in hand. Yeah. One of you has got the egg. One of you has got the costume or the fantasy.

Tim:

They were always really fun the Halloween nights, particularly on base or in the area that we would do Halloween where all the military men were. I think there's a camaraderie between military kids and military men and women, people who serve in the military. It is a weird coming together of this kind of like dressing up, going around each other's houses, taking sweets with them. And there just seems to be this kind of strange little tiny little part of America amongst a very East Anglian landscape. It's very, very odd. [So odd] But yeah, no, those all of those things I think America does better. I think they do seasonality better, they do festive things better. They, they don't have this kind of English worry. [worry]

Charlie:

And I think it's something to do with not wanting to look over the top. Do you think having this dual cultural experience has influenced the way that you look at the everyday or the bigger picture kind of thing? We have come to the end of part one, so feel free to take a break from your listening practice, but if you're happy to keep going, then we're now moving on to part two of this episode. Thanks so much for being a premium or Academy member and enjoy the rest of the show.

Tim:

I think it has had a significant impact. And it was only I think it's only until you get older that you start realising how kind of odd it was, because I think particularly for me, I went into the music industry, that was a thing that I did and then went into, you know, film making and things like that. It's always quite odd because I think you never really feel at home anywhere. You're half of you is in England and you feel like, okay, I've got an English accent. I think about things in a very English way. Like I suppose in terms of cultural things like football is very important to me, like soccer is important to me, American football less important to me. But I think it's kind of you have these kind of things that make you quintessentially English or you at least you hope. And then you have this other side of you where it's like, I've got all those people and all these people who made me and are a part of me and as part of my DNA and also things that are really significant memory-wise and nostalgically to me, which are American. And also what I found particularly interesting when I was over there recently was that you sit on a dinner table with all of these people who are just you in different stages, like they have like 50% your humour or 35%, you your kind of ability to get on an emotional level with someone quite quickly or whatever it might be.

Tim:

And you notice these kind of significant things in your family members and that for some reason for me now feels American, like I associate big families, big connection, big all like all of these things which I consider very pure and lovely and family orientated as American and I consider brotherly just me and my mum type spirit, very close small family as English. So it's quite odd. Extended family I don't see as an English thing. I see it as an American thing. And that's purely because my experience and I think that is probably consequentially subconsciously why I have ended up with an American, you know, because I find this kind of deeper connection in people who aren't English essentially to go, Oh, okay, I can see how that person would play a part in my life in this other person wouldn't. I think that it definitely has this kind of far more deeper impact. And I think you could ask anybody there's a lot of people in London that I know who are have grown up in England but were born in Africa and hadn't seen a lot of Kenya or Tanzania or wherever they've sort of come from. And they feel this real big drive towards this other culture. And they they have to experience it in small doses, these tiny little kind of segments of life. But it feels more important than that. It feels more significant than perhaps the other half of them, which is English.

Tim:

And I definitely feel like with it's always interesting to look at the dataset, which is my three brothers, like my oldest brother loves American football. Every time he goes to America is like, I should live in America. I feel American. And would probably say, the minute you ask him where he's from, half-American half-English. My middle brother - English, quintessentially English. [the Essex one?] English music. English films. No the Essex one is the oldest one, ironically. My middle brother - quintessentially English. English films. English music. English culture, English, lives in Derby. And then when it comes to me, I'm this conflicted and I used to consider myself a little bit of an alien in the kind of sense that I'm like, Oh, I don't really fit in anywhere. This is annoying. I can relate to the Americans, but not enough because I wasn't over there or I wasn't in the schooling. I can't relate to the English lot because the minute I say I'm half American, they're like, Oh, okay, that's cool. And then I've dealt with that. And I found a lot in things like the music industry or when I moved into film or advertising or wherever it turned out to be that I would use it as a bit of a superpower to go, Well, okay, if I have an American client, I'm immediately upfront with, "Hi, I come from Buffalo originally" and it's an immediate talking point. If they're English, I won't mention it.

Tim:

And same with music. It's like, you know, it allowed for a level of kind of exploration across English and American music and finding an identity there. And so I think it has a significant impact. And people wouldn't presume that. I think I think people would think, Oh, okay, so you went over to America a lot and that's nice. And then that's where it ends. But then you go, well, no, you know, that's a significant thing of my life that I've never really. And you also feel a little bit, it's kind of ironic and it's put through this kind of did it through such a wonderful, facetious filter of 'which side will he choose?' at the beginning. But that is how I feel a lot of the time. I'm like, Am I like exposing being too quintessentially English? Have I immersed myself too much in English culture and not allowed for that American life to be a part of it significantly more? Have I celebrated Thanksgiving enough? Have I been over there enough? Have I? Do I enjoy the sports? Do I enjoy the culture? Do I enjoy the politics? Do I? There's so many different things, levels to it that you just feel like you've neglected. And, in exchange for just going to school in England, it's an odd one. And you look at the RAF brats who went to school in America and their entire personality is American that you go, Is that the only?

Charlie:

Sorry to clarify, they had a British. Military base in America. You meaning the RAF brats?

Tim:

No, no, the RAF brats in England. But they spoke American. They enjoyed American culture. They were always.

Charlie:

Yes. The two girls.

Tim:

Yeah. Identified as American. [Yes] You know, and it was kind of interesting. I had a friend called Eric who is the polar opposite to me, and we grew up two minutes apart, did everything together. We did skateboarding, football. We did like these kind of weird things where we'd go, that's quite American, that's quite English. We played cricket, but we'd also play baseball. And it was like, [wow] yeah, it was this odd kind of thing where we would just find the balance. He went into the American Air Force and became and just adopted the American thing. Even though we went to the same schools, embraced the same levels of culture, did the same things. He just took a moment in his life where he went, No, no, no. I think I'm more American, served his country, aka America, and now just lives in America. And I went, I really like music and the arts and I'm going to be English. And I must have chose that direction at the age of like 15 when we drifted apart. And so it does make me think, you know, with all these kind of people and I think about Becky and Tanya and how Becky is in America, Tanya is in England. They obviously had the similar thing, and they're sisters. And that's, you know, [wow]

Charlie:

I was thinking that it would have given you I know we have a lot of musicians, but did it give you the courage to be a bit more expressive with the arts being, having that American side to you? Maybe your father encouraged you to be more expressive because British culture is quite the opposite of [Yeah] in that regard.

Tim:

It's interesting because I think essentially what American I think led me to what what I think I garnered from it was less from arts and more about confidence. And you would walk into a room and people would be unashamedly positive or like, you know, which is alien to English people. [Yeah] Or they would be quite expressive my family, about love and about doing the arts or whatever it might be. My dad was always relatively quite chilled out and had adopted English culture on such a level that he found a nice balance. And I think that the yeah, the biggest thing I got from it was confidence and not feeling too ashamed by being the positive, confident one in the room to make sure that everybody else felt comfortable or in a lot of cases uncomfortable. If you're in England, that's always difficult. So, I think it's interesting because you see people like Katie, who's obviously been on the podcast, American but been in England and adopted English culture and loves English culture, like was interested in English culture growing up, which is always fascinating to me going, Oh, don't you hate it when American people are so positive? And I'm like, No, I don't think so. Like, I actually quite like walking into a room and someone being like, Hey buddy, how's your day been? Rather than - hello, And it being awkward, it's super interesting to think the differences between, you know, us and them.

Charlie:

Do you appreciate what a Brit would probably say, the cheesiness of an American personality, The stereotype?

Tim:

Yeah, I do. And I think it's because once you get over the fact that they could be hating you but still being positive. [Yeah] You know, that's always a risk. What I realise is the key signifier is that English people will also do quite a similar thing. I guess you can just see through it a little bit more, whereas at least with people being slightly more positive, yeah, I don't find it as cringeworthy. My middle brother Matt finds it incredibly excruciating. He finds that really unbearable for me. I think that having grown up with so many Americans or half Americans is a kind of part of my DNA. So I just go, No, I kind of get it. I can see where the parts of it, you know, lies and where the negative side of it lies in English culture. Regardless of it, I think it's not that harmful for people to be positive. So I usually see it through that filter.

Charlie:

Yeah. Nice. Let me read this one. In your opinion, which stereotypes about British or American people have you found to be true and which are wildly off the mark? I quite like that one.

Tim:

Yeah, it's a good question. The stereotypes we just spoke about, Americans are slightly more positive, slightly more confident, I would argue, and slightly more just like in a room, slightly louder, like there's just a particular Americans.

Charlie:

I've Googled this a lot and tried to figure it out. Do you know why they're they're louder.

Tim:

This sounds awful, but I think so my family are Irish Americans. Because you're never American. American, really, are you? Unless you're Native American. That's.. If you're Irish or Italian American, both of those countries which I've had significant connection with, have a lot of Irish friends, have a lot of Italian friends. And I feel like both those can be quite loud basically, or like at least expressive. Loud is the wrong word. So I wonder whether it's this thing that just when you've got. An Italian and Irish person and they both walk into a bar. [Sounds like a joke] Yeah, exactly. Yeah. And I just feel like that would perhaps create a little bit more kind of expression and allow for two identities to kind of contend with one another. Whereas an English person has always very significantly stepped back from the noise. [Yes] You know, that's the thing. As do Nordic countries, very subtle, very kind of understated people. So I do feel like when you throw the Irish in the Italian thing into the mix, maybe that's it, you know.

Charlie:

I like that theory. It could be very rude and offensive [It could be] to three cultures.

Tim:

Absolutely.

Charlie:

But I like it. So sorry, guys, if you're offended by that, it's better than the - how do you pronounce that website? Quora? We have come to the end of part two now. So again, feel free to pause the episode to take a break from your listening practice and come back to the last part when you're ready. All right. So moving on to part three now. Enjoy.

Tim:

Quora. Yeah.

Charlie:

So many vowels. Quora.com. Yeah. The one that everyone asks crazy questions on. I've seen people ask that question, and people have crackpot theories. Yeah, I'd say yours is the best crackpot theory out there.

Tim:

And I would never mean it to, like the Irish and Italian of my life are the best people I know. So I think that and also what I love most about Irish and Italian people is that they will often tell you how it is. Like I've never known being drunk with an Irish person them to just like be understated and be quiet about a subject matter which is passionate to them, same as Italians. So I just wonder whether that stems from... But I think that with the Americans there are far more positive. There is a culture of positivity, there's a culture of celebrating one another. In England, there is nothing funnier than someone failing. There is nothing better than a smug, positive person failing miserably. Like everybody rejoices and goes, Well, shows you right for being positive. Yeah. In America they will hold you up and they will go, You can do this. You are fine. You are absolutely fine. You're absolutely gonna smash this. In England. Yeah, they are waiting for your downfall and I think everybody's quite conscious of that. Therefore doesn't take too many risks. And the ones that do are ridiculed, you know, I just.

Charlie:

Yeah. Even if not to the face behind their back. [Yeah]

Tim:

I think those are the key, like the obvious things that people consider to be the stereotypes that I think live true in my experience. I think the thing that I always disagree with that people think is a stereotype is humour. I think Americans have over at least the last 20 years, got a humour that is very akin to English humour, significant to a lot of comedies that have perhaps crossed borders like The Office and things like that. But I think the awkwardness and allowing for the silence and the kind of cringeworthy stuff has started to be built out. The things that I see primed with Monty Python come through comedians in America now in such a significant level. [interesting] There is a lot of people think American culture is not understanding English humour. There's this big trope of like, they don't get it because it's English. They don't get it because it's American. I don't think that's true.

Charlie:

You don't think that's true?

Tim:

But perhaps because I'm half American English, I just understand it, you know.

Charlie:

You know the example that you used of The Office, the British office, I would say, has much more awkward pauses. [Yeah] Less story built into each character. And it's more about the deadpan, horrendously uncomfortable situations that David Brent puts himself into. Whereas I think the American Office, which I absolutely love and I watch pretty much every time I go to bed at the moment. I think that's a little bit more about the, the relationships that they have, the storytelling, and obviously they've got nine, ten seasons, maybe even more. [Nine seasons. Yeah] So they've got time to build that into it. But I think in the first two seasons they had to change a lot because the humour wouldn't translate in the same way.

Tim:

Yeah, that's interesting because the first season of The Office absolutely is that I think that's a, it's an interesting thing because I think you will still see American comedians being massively inspired by English comedians like Ricky Gervais has made such an impact, but also people like Eddie Izzard or whoever's gone over there, Billy Connolly still have American audiences. And Monty Python was huge, huge in America, you know, at least at the most kind of impactful kind of comedy that a lot of American comedians would say. And same for English. Like they would look over to America and be like, Wasn't Seinfeld good or wasn't, you know, Larry David's or whatever it might be?

Charlie:

Yeah, Larry David Yeah.

Tim:

So it's kind of I do feel like.

Charlie:

Sorry. That's actually really uncomfortable. Awkward.

Tim:

Larry David Yeah.

Charlie:

That's, yeah, that's fair.

Tim:

Curb Your Enthusiasm is like, that's a lot of awkward pauses, isn't it? [Yeah.] And it's kind of interesting because also, you know, you look at the kind of docu-style and how that translated to Parks and [rec] what's it called? Yeah, Parks and Rec, that has the documentary style and things like that. And they have the awkwardness built in. And so I think it's been a relatively new thing, but I think it's changed significantly. And I think Americans are now more up for poking fun at themselves. And I think English people, English comedy, perhaps there's a level of Americanisation that happened to us earlier on with sitcomming and things like that, which I feel like would have been an American influence, particularly with things like Seinfeld or Frasier or Friends you see come through kind of English comedies. I think that's a trope that should be stamped out and shouldn't be a cultural signifier. I don't think humour stands as much as it does anymore. I think positivity and those kind of things absolutely will return.

Charlie:

So you've done a bit of comedy yourself. You've done comedy, you've done stand-up, haven't you? [Yeah] So you've, you've experienced a lot of that world and I just want to deliberate over whether it's the that world that you're referring to in reference to British and American or the everyday person.

Tim:

Interesting one.

Charlie:

I think when I went to, when I'm in a room with a guy in the UK, that sounds just like when I came into your flat, I think the first thing we wanted to do was make a joke.

Tim:

Yeah, that's true.

Charlie:

And I don't think that's the main aim for Americans. I'm obviously speaking just as a British person without any experience as an American. I felt like that wasn't the first thing in their brain. [Yeah] When they're trying to start a conversation up.

Tim:

Yeah, it's interesting. I think that particularly with the circle that I have in America or the American friends I have, it is the first thing [is it?]. So even still with that. But I think American humour perhaps is slightly more taking the mick. I think I would often come into, if it's my dad and my Uncle Paul or anything like. Like my Uncle Paul is one of the funniest people that I know. So it's difficult. So it's but he's got a very dry English through an American filter kind of thing, and he doesn't have much to do with England. He's obviously got nephews and who are English. He is defiantly American again, another military man, things like that. I think potentially military culture allows for a lot more banter and things like that, and you have a lot more exposure to English people and things like that. So maybe that's it. What I've found is when you go into a place and, you know, Katie's dad's a good example as well, he will do anything to crack the joke. And I think, you know, punchlines are significant. And I think the first thing, we've only met over phone call, so I'll let you know how it goes, you know, in a few months time. But the first thing that we I noticed we did was either try to talk about sports or like try and make each other laugh and be quite silly. I think it's yeah, it's an interesting one, man, because I know what you mean. I think early on, I would say maybe 15 years ago, I found the humour thing very difficult. They didn't get me at all and I was young. That made me incredibly anxious, you know, and I was like 15 and being like, Why are they not laughing? And then you got past 20 and then and then it just seemed like because of mass culture and the borderless Internet type nature of streaming and things like that, I think it just got easier and I think people got funnier.

Charlie:

You may have got funnier as well.

Tim:

That is probably the answer, actually.

Charlie:

That's interesting. Yeah, I might have to adjust my assumptions there as well.

Tim:

Just quora it. Just look at Quora.

Charlie:

Yeah, guys, just stop this episode. Quora it. Yeah, I can't even say it. How have your experiences influenced your relationships and connections in both cultures? Like, have you felt more accepted in one culture over another? Perhaps?

Tim:

I think that it's easier to be accepted into the culture in which you exist, like the place that you live. So I think that makes sense on the surface, that having an English accent and having an English style to certain things make sense that I'm English. I don't think it comes up that often, and I think it's a weird one, especially with American English. They're so close culturally. Obviously, language-wise, there's so many kind of connections to it that actually it's quite hard to to separate those two things. So I think it's easier to be accepted in England. It's much harder to be accepted in America. I think you're immediately the English person in the room, which particularly in small-town America, my family have gone from New York to New York State to Colorado to Arizona.. It's spanned quite a lot, but predominantly small working-class towns. These are not like it's not the Denvers or anything like that. It's like the small towns in Colorado, small towns in New York and things like that. I think it's much harder because actually a lot of small-town America are a bit like, Wow, that's an English person, you know, 14 years ago who came into this cafe but or this restaurant, it's slightly odd. I think you are immediately out of place when you're an English person in America. And I think that works to your benefits because I think, you know, people are interested in you. They want to talk to you. They want to work out why you're in America, particularly a small town in America. When we stayed in Arizona recently, we went to a place called Prescott. I don't think there's been an English person there, you know, for years. When we went into a bar, they were like, Wow, okay, tell us about England. The biggest thing they found was, what do you do? Do you hunt? And we were like, No. And they were like, But you have guns? And I was like, No, okay, So this is a huge thing.

Charlie:

Oh, right. I was I was taking that a bit different. I thought you meant they didn't understand that there was any professions other than surviving. So you hunt for your living.

Tim:

Yeah, no, just the sport. Like, they just didn't get that they were like, one of the bar guys there was showing me this big cat that he had shot and he was like, How does this make you feel? And I was like, Kind of weird, man. I don't know. I don't know what you would say.

Charlie:

Do you mean like a domesticated pussy cat?

Tim:

Yeah not like a house cat. No, thank God. I would have thrown his phone in the, out the door, but it was like a massive, like, I guess like a snow leopard or something. [Wow] You know?

Charlie:

And then you showed him the pussy cat that you shot.

Tim:

Yeah. And I was like, What do you think of that?

Charlie:

No cats were harmed. Well, no one was, but no.

Tim:

One large cat was harmed.

Charlie:

They're actually rarer.

Tim:

So we should exactly be more concerned. And it's harder because especially when you go into these kind of towns which, you know, really embrace that kind of culture of hunting or quite what they would consider to be, you know, I guess working class, blue, like blue-collar American traditions like hunting. They find it very alien that you go, oh, no, we really disagree with guns. And they go, What? And that's the biggest thing. And that's when I feel like my most English, when when those kind of things come up. [Yeah] Guns or health care or whatever it might be.

Charlie:

Yeah. The health care one is a huge one. [Yeah] Nice. Do you have any advice for anyone still growing up in a bicultural environment? So I'm imagining maybe the military base, a younger version of you. Would you sit him down and say, Look, boy or girl or, you know, whatever you like to call yourself nowadays. I've not got a problem with that. But I do have some thoughts. And here they are.

Tim:

Yeah, I would I mean, mainly I would just say to embrace both sides much more. I found I was so caught in the middle that I was more anxious about it all.

Charlie:

About where you land, who you are, rather than just being like, Well, I've got the best of both worlds!

Tim:

Exactly. Yeah. You've literally, I could, I wish I would have appreciated base more and I wish I could have gone over there and I would have eaten much more Taco Bell and I'd have eaten, bought much more kind of the cereals at the time. It wasn't like when big superstores would just import it in. You'd get an American section. These were like things you couldn't get unless an American plane put it in a base.

Charlie:

Mental that Taco Bell. You could go to a Taco Bell in England.

Tim:

Yeah.

Charlie:

So your advice is go to Taco Bell more.

Tim:

Exactly. [Yeah, good] Thank you. Yeah, that is the condensed version of what I'm trying to say. I think it's just embrace it more. And we should have enjoyed Halloween more and I wish I'd have enjoyed Thanksgiving more. And you know, a lot of those times when you particularly when kids find that as a differentiator to take the Mickey a little bit. Yeah I think actually I'm a bit like I wish I'd had I wouldn't have been too bothered by that. And that probably made me more anxious to embrace the American side of things. And also, I think you hit 16 and you go like, particularly in the teenage years, you go, What actually am I? When you're in the music industry, which I was, you're front and centre to go, this is who I am, I'm going to express myself. And I was in a specifically very Americanised kind of genre of music, which was considered pop punk, blink182, Green Day's, all that kind of stuff. You're fighting this thing of going, I love that. Because it's part of American culture and I really like it. But I'm an English person in this, but I have got a justification to like this a little bit more than everybody else in England, because I noticed it earlier. I actually do understand the references that they're talking about and all that kind of stuff.

Tim:

I was so anxious about all that kind of stuff that I just didn't get to enjoy it. And I think now I find it particularly interesting for conversation starters. And as long as you treat it as a conversation starter, then it's good. And I think there's a lot of dilemmas that you consider where you have actual family members going through health care or they going through, you know, laws or whatever it might be that you massively disagree with. And it's such a different political spectrum and societal spectrum to what you're used to in England, potentially in certain towns or cities. And I think that it's important to realise that you are where you live, essentially. I'm in London and I'm in Chiswick and there's political and societal things that affect me directly right now. In America there is not too much control I have over that kind of stuff. I'm not immersing myself in that culture and therefore I technically don't get much of a say because that's up to a Democratic decision to make those kind of decisions. Whether I agree with them or not, I think we can all read between the lines of what I'm talking about. [Yes] You know, and I just think.

Charlie:

Build more Taco Bells.

Tim:

Exactly. Thank God you spend your money more wisely on Mexican fast food.

Charlie:

I know what you mean with that.

Tim:

It's very difficult because you get it with the Australian side of things. Katie gets it with being in London, but being American, full American, you know. I get it so much with America and wistfully kind of hoping for that kind of part of my life to be answered in some way. But the reality is, on a day-to-day basis, I wake up, I go to Waitrose in Chiswick, that you have to just accept the fact that actually there's a lot of kind of things that culturally you can't make a huge impact on when it's on that other side of things and that actually you have to, you can only see it from half the perspective. And that is I guess the point, this whole conversation. I feel like I get half the perspective of everything, which is good in some ways because I get a 360 perspective of half American and half English. But when it comes to understanding English culture on the granular level or American culture and the granular level, I probably don't, right? I could just get this weird mix of things. I guess that's a superpower in itself that you go, okay, well, at least I can understand both worlds. On a more granular level. I can connect with Americans and English people. I think when it comes down to it, realistically, I felt very misplaced. I felt very not at home anywhere. And I think the biggest thing I learned was, your home is where you make it. And that happens to be currently London, Chiswick. If I end up in New York, then I will embrace that as my home. And that's and.

Charlie:

That is a nice piece of advice to a young lad on the edge of a military base, confused about what road to take. [Yes] Yeah. Yeah. Very nice. Yeah, I like that. Okay. And finally, is there anything else we haven't covered that you love about being a bridge between these two cultures?

Tim:

I haven't spoken about this all that much. I think this is a good chance to speak about it. But there's this fast food restaurant called Taco Bell.

Charlie:

Do tell me more.

Tim:

Thankfully, England has adopted it and we have some in England now.

Charlie:

Do we actually?

Tim:

Yeah. [Oh, really?] Yeah. Yeah. You can get it on Deliveroo. The interesting thing about it is that it gives you, and this is like culturally a thing that happens across things like TikTok and Instagram - this is like the ongoing joke, is that Taco Bell will give you such an upset stomach. [Yeah] That it's like you take it as like a bullet to the head. You go, I'm going to eat it. I know I'm out for two days. That's the only thing really, that bridges the gap. Now it's in England. No, I don't think there's anything too much apart from fast food Mexican food.

Charlie:

I mean, you've mentioned a few. The fact that you are able to appreciate both sides of things, the references, you get them. You're not confused. I like that.

Tim:

Yeah, I think that's good. I think sports - it does open up your kind of perspective on a lot of things. I do feel like I can appreciate baseball and NFL and hockey to such a degree because I got to see them quite young. [Okay] And as a genuine sports lover, someone who can just turn on sports and go, Oh, I'll get it. I'll be obsessed with this for a little bit. I think that that is a really lovely bonus where you get to actually have a team that you belong to. So like Buffalo Bills or Buffalo Sabres, the hockey team or, you know, whatever it might be, having an actual home like an actual team that you go, Oh no, I like them because I grew up there and I got to, you know, in so many ways, I think that's a really nice thing that that gives you a balance as well. A lot of people just choose the team because they like the players or they like the colours or whatever it might be. I actually get to choose the teams, both terrible teams, right. Both are awful teams, but I get to live and breathe those teams because I have a vouched interest and connection to them. So yeah, that's a nice thing.

Charlie:

Yeah, that is nice. Beautiful. Well, I think we will leave it on that note. Thank you very much, Tim. [No worries at all] It's been a pleasure. [All good] Thank you for sacrificing your Friday afternoon slash evening for this.

Tim:

Of course. Happy to. Big fan of the podcast and what you do and I think hopefully this will be fun.

Charlie:

Oh, it will be cool. All right. Thank you guys for listening to the end of this one. If I can, I'll try and get Tim on once again shortly. But yeah, thank you and goodbye for now. There we go. The end of part three, meaning the end of the episode. Well done for getting through the entirety of it. Make sure you use all of the resources available to you in your membership. Thanks once again for supporting the show and I look forward to seeing you next time on the British English podcast.

Get the FREE worksheet for this episode

Want the transcripts?

full glossary and flashcards for this episode!

-

Downloadable Transcripts

-

Interactive Transcript Player

-

Flashcards

-

Full Glossary

Transcript of Premium Bonus 047- Transcript

Charlie:

Hello and welcome, ladies and gentlemen. Boys and girls. Well, no. Mainly ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, not really advised to listen to this because there's sometimes some swearing. But yes, welcome to yet another scintillating episode of the British English podcast. As always, I am your host, Charlie Baxter, ready to take you on a fascinating exploration of culture, language and the riveting places where they intersect. Today's theme agent of Two Worlds The Mysterious Life of a British American Spy. A deep dive into the unique experiences of those who've lived a life between the UK and the US went on a search for one of those people who really do see the 41.1 million square miles of Atlantic Ocean as a mere pond that they pop over whenever they feel like it, and found an individual who could well be a double agent. But which country is he truly serving? Hopefully, we won't need to torture him to get to the bottom of it. But whilst storming his flat in London and setting up two microphones, I did pack my trusty waterboarding rag and bucket just in case. Ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming our guest, a man who personifies the British American connection. Born to a British mother and an American father, a mr. Tim Hyland. Hello, sir. How are you doing today?

Tim:

Yeah, very good, thank you. That was an amazing intro.

Charlie:

Well, thank you for letting me take your flat. Yeah, Come in rudely and not kick me out. It was very British of you. Is that an admittance to what Secret Service you are actually truly working for?

Tim:

I tell you what, actually, I think it's quite American to just accept, particularly my family. You would just accept somebody coming in. It's the best of both worlds, of both anxieties to tell people to leave. No, you're welcome here for the next few hours. And then I'd like you to leave. [Okay] That's the English version.

Charlie:

Yeah. Good.

Charlie:

I've got a question for you. I mean, I've got loads, but to start with, I've got one that I've always wondered, considering you've obviously grown up with a cup of English breakfast tea in one hand and an American hot dog in the other. How does it taste? Dunking a hot dog in your tea. Do you encourage everyone to try it?

Tim:

100% encourage everybody to try it at least once in their life. I think it's the delicacy of a half-English, half-American person. We all have a forum that we speak about our dunking abilities on, and that's one of it. And it's delicious.

Charlie:

Yes, I imagine the liquid would drip quite quickly off the skin of a hot dog.

Tim:

You'd be surprised.

Charlie:

Okay, so apart from being astonished by the absorbance of a hot dog, can you share with us a bit about your upbringing and how did growing up with parents from two different cultures shape your early years?

Tim:

Absolutely. My.. So my mum is English. As you've sort of stated, my mum met my dad, my dad was stationed, he was a military man and he was stationed in a place called Mildenhall. And it's quite a big base American base in England.

Charlie:

Where is that?

Tim:

In England, In Suffolk, in East Anglia. [Okay] He sort of met my mum on a sort of night out. All the people from the RAF would go to the local nightclub. My mum met him. I think that's through the manner of which they met.

Charlie:

The RAF. They're an English, the Royal Air Force.

Tim:

Oh no. So it's actually AAFES which is the American Air Force.

Charlie:

What did you just say? Did you say..

Tim:

RAF. But that's just what we sort of refer to it as.

Charlie:

Oh, I see. So you used the British thing.

Tim:

That's an interesting thing I've never even thought about. We would say AAFES, which to be honest with you mate, I have absolutely no idea what it all means.

Charlie:

Sounds a bit weird to be honest. AAFEES.

Tim:

Exactly. That's why I don't use it.

Charlie:

RAF is very bold.

Tim:

Yeah. Plus, if I said Athies to you, you'd go. There's more questions.

Charlie:

Yes, we'd be here all night. So again, do you see that often? You know these cultural references and you adopt the right language for the right audience?

Tim:

I think more so growing up now, I'm sort of I've lived well, been in England more than America. I would say that I would adjust my my language more for the Americans than I would for the English. But there was a lot of times when we were younger, like Athies, like RAF, like even things like base, if you said, Oh, we're going on base this weekend, people would be like, What is base? And then I'd obviously have to go, Oh, okay, that's place where military stuff. Yeah.

Charlie:

Go back to where they met.

Tim:

They met in a little town called Newmarket. And basically it was a bit of an odd one, you know, because around that time in the 80s it was considered slightly odd for a lot of females would go to the base to marry an American man, to get out of the little town that they were in. That was kind of through the manner in which my mum was filtered, but that's what she experienced from other people. But that isn't actually what happened. [okay] And it kind of accidentally happened. They moved to Ipswich and my dad, we spent a lot of time on, you know, what was considered and what was often referred to as American soil, which was the base life, which was this incredible military base, which everything was American on it. So absolutely.

Charlie:

And it's in England.

Tim:

In England, there's a bunch of them around. [Wow] And they would have bowling alleys and restaurants and everything would be American. They would fly over ingredients.

Charlie:

We've got that - bowling alleys.

Tim:

Yeah, well, not American ones. [No]

Charlie:

What? So they would ship over the American-style bowling alleys?

Tim:

Yeah. And just absolutely everything you could think of they would fly over. They tried to make it as much home away from home as they could for the military men. We kind of, you know.

Charlie:

Did they like that? Because, you know, being abroad is quite an exciting part of life, isn't it?

Tim:

Yeah, it's it's an interesting one. I found this a lot with Dad. I think there's levels to which you can enjoy English culture and immerse yourself, but at the very foundation of it all, you are American and you love Taco Bell. So I think he really adopted clever. He loved pop culture, loved football, really adopted all these kind of things. But the reality was if he ate in a McDonald's in England and then he went half hour down the road to the base and ate the McDonald's there, it would taste completely different. [Wow] Yeah. Yeah. It's kind of [wow]

Charlie:

Well, so they actually shipped in different meat for that McDonald's. Do you think?

Tim:

That was a rumour amongst the RAF brats which we called ourselves. People who had to kind of toe this line of English and American culture.

Charlie:

That's so confusing.

Tim:

Yeah. The room was they would fly in and I think I reckon would be able to confirm it, but I don't know. But it's a better story, you know. [Oh yeah] Always print the legend. They would fly in the actual Taco Bell, meet the actual actual spices, everything.

Charlie:

Wow. Did you live in that environment or did you live outside of that?

Tim:

Yeah, 15 minutes outside of it. It was a choice that they both must have made to go.. when education came up. You can obviously, there's a school, a high school on base and there's football teams and there's, you know, everything.

Charlie:

And by football, what are we?

Tim:

American football. [American football]

Tim:

Yeah. [Wow] They would have absolutely everything that was potentially probably a big conversation that my mum and dad had that I obviously wasn't there for, and yet England was chosen.

Charlie:

But they didn't, surely wouldn't have gone to the extent of building wider roads and bigger cars.

Tim:

That's an interesting one because it was a military base. You would have this weird mixture of a lot of military vehicles and then a lot of the American military people serving the military would have cars all over. A lot of them wouldn't want to. So when you go back to these kind of places near bases like East Anglia, you will see like a pickup truck just randomly on the road with the wrong side, you know, the steering wheel on the wrong side and everything. I think you have to be really committed to the cause. If you're going to do that, you have to really.

Charlie:

Yeah. That's not just what do they call it? Not a stint. What's it called? A tour. Do you do tours to this place or do you live there? And then you go on a tour to an actual active country.

Tim:

I get the impression tour's when you go to a place of conflict, which my dad was very much involved with, did a lot of tours and England was where he was stationed. So I suppose because the massive difference being that this is a place to be be closer to Europe, to protect, have American bodies on ground, to protect Europe, basically.

Charlie:

God, it's such a different world. I mean, my parents, one of them is a teacher and one of them is a therapist. This is, I have no contact with Army life. I mean, my granddad was but I think all granddad's were to some extent, weren't they? Forced into it someway. [Yeah] Okay. So you grew up 15 minutes away from this American military base. [Yeah] And you went to a school that was English [Yeah] curriculum. British curriculum. But you had lots of American friends?

Tim:

Yeah, well, it's kind of difficult because I guess this is the point of the conversation. Like, the friends that I had were often half American and half English. [Of course] The ones who were taught on base would be what we called ourselves RAF brats and stuff. Military brats were more often than not half American, half English, and they, everything would be dictated by where they were educated. If they were educated on base, I'd have a lot of friends who were educated on base. They would all speak in an American accent and they would all be far more ingrained with American culture than they would English culture. And with us, because we were educated in England, literally 15 minutes down the road, all the same friends. We grew up going to the same gigs, going to the same nightclubs, doing all that kind of stuff. We spoke, you know, in an English accent and kind of immersed ourselves in quintessentially English things. And so it was just that very small differentiator. Living on the same in the same county, 15 minutes apart, but such a big distinctive on the surface thing, you know, American accent, English accent, dressed American dressed English, you know, all these kind of different nuances of culture. [Yeah] Yeah.

Charlie:

Did that ever cause conflict amongst peers? Like at that age, we're quite we're wanting to conform to the norm, aren't we? [Yeah] Did that make some people be like, What are you doing speaking American?

Tim:

Yeah, it was. What I found was a lot of the ones who had grown up with American accents, despite being in England, would really double down on their American accents. Okay, Really double down on it. I had a couple of friends called Tanya and Becky who literally like my, our dads worked together. You know, we lived not too far apart. We met in our kind of teen years and realised we were at the same bases and things like that, ate at the same places. They were very American compared to me and I remember speaking to them about this and being like, Why is it that you feel like you tried to retain that American accent despite clearly being surrounded by more English people? And they said that they themselves definitely doubled down on it, definitely found it was too confusing to have this weird accent that was a kind of transatlantic, you know, middle ground. They just chose sides. They just kind of adapted. Whereas for us it was slightly easier because I think it always became a bit more confusing when you would people would meet Dad or they would go, What are you doing this weekend? And I'd be, We're going to a barbecue on base or we're going to watch the football or whatever it might be. I think that's potentially where the confusion started coming in. And I think because American culture was so huge in the 90s the late 90s, American Pie was coming out and Blink182 was the biggest band and things like that.

Charlie:

American Pie is one of the biggest things of America that came out of America.

Tim:

There's a song about it that definitely helped the cultural influence.

Charlie:

Of Yeah, I know what you mean. Especially their music, I suppose. I wanted to ask about them. If they were sat here right now, would they say that they're American? Those two that doubled down on being American when they were ten or however old you were?

Tim:

Yeah, it's kind of interesting. Tanya stayed in London, lived in London, and Becky moved back to America. I feel like despite that, they would both still say American and their mum was English, their dad was American in the same situation as me. Sit me down here. I would say, I tend to say I'm English, but if there's a longer conversation, I'd say I'm actually half American. That's the kind of distinction. I think the base has a lot to account for for that kind of stuff.

Charlie:

Do you think accent is like a fingerprint of your identity or do you think we should negate that totally? Is that a very simplistic view?

Tim: